UAE, other Gulf states exposing migrant workers to potentially fatal temperatures

COP28 hosts should lead the way to protect workers’ health and lives in the face of alarming projections

Extreme and rising temperatures in the Gulf states are placing migrant workers across the region at acute risk of potentially fatal heat-related illnesses and injuries, a new report from the Vital Signs Partnership has found.

The report draws on new climate change projections for the region that left one Kuwaiti climate expert “horrified and deeply alarmed”, as it shows that Gulf states are set to experience hugely significant increases in the number of extremely hot days even if global warming is kept at 1.5ºC, and potentially catastrophic increases if global warming reaches 3ºC.

The news comes as the Gulf prepares to host COP28, the crucial UN global climate conference, with the UAE leading negotiations as president. In May the UAE announced that for the first time a day of the COP talks would be specifically dedicated to the health impacts of climate change.

Nicholas McGeehan, co-director of FairSquare and member of the Vital Signs Partnership, said:

“The climate change projections for the Gulf in this report are as horrifying as the personal accounts of the workers exposed to 2023 temperatures in countries like the UAE, whose COP presidency places it in a unique position of responsibility this year. It is necessary and welcome that there will be a focus at COP on the health impacts of climate change. As part of that discussion, the UAE and other Gulf states should be prepared to address the appalling impact of their systematic failure to provide basic protection to the people whose labour sustains their extremely wealthy societies.”

Working in extreme heat

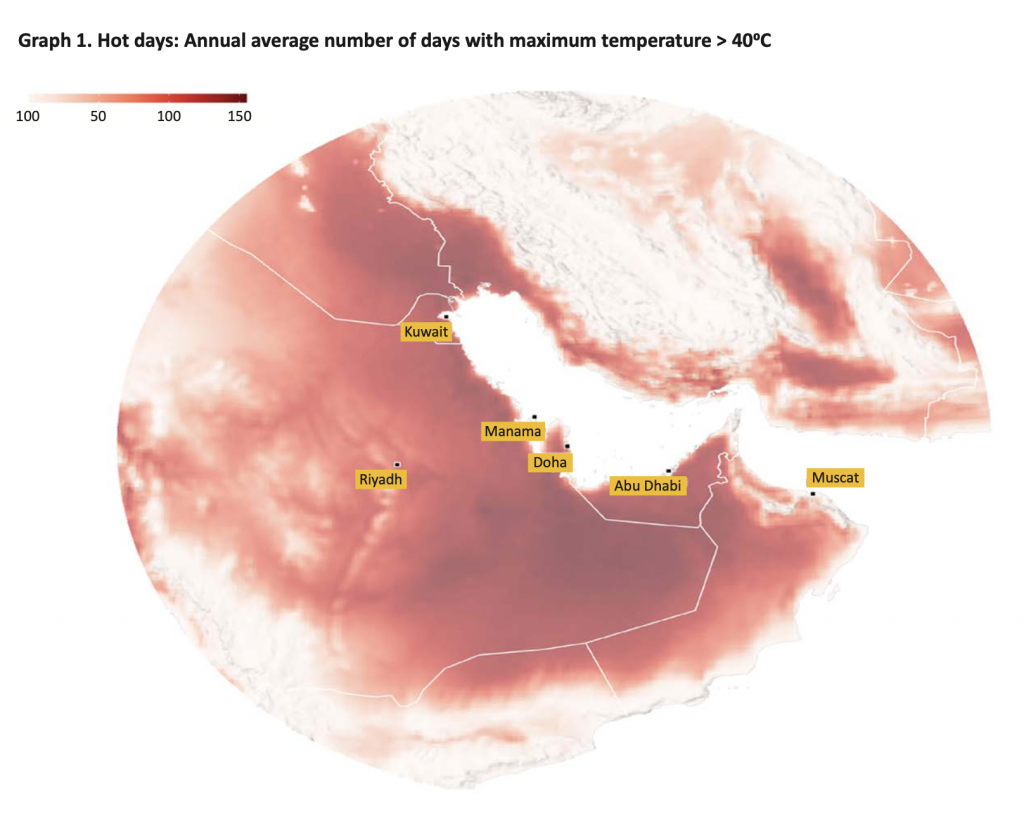

In most parts of the Gulf, there are between 100 and 150 days when maximum daily temperature exceeds 40ºC. For the same period, the annual average in New Delhi is 24 days. Extreme temperatures are not rare “heatwave” events in the Gulf, but present for three to five months of every year. Exposure to such a climate can create cumulative stress on the body and risks exacerbating the impact of respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and kidney disease. Rapid rises in heat gain can cause what the WHO describes as “a cascade of illnesses”, including heat cramps, heat exhaustion, hyperthermia and heat stroke.

Ganesh, from Nepal, went to UAE in 2018 to work as a lifeguard, and spent 12-hour shifts at the outdoor rooftop swimming pools of apartment blocks. “The ground was so hot I couldn’t touch it with bare feet,” he recalled. “It would burn my skin. You can’t imagine how hot it was.” Ganesh developed numerous health issues after he returned to Nepal. Doctors diagnosed kidney failure, which he suspects resulted from his substandard living conditions and abusive working conditions in the UAE.

Construction workers are particularly at risk of heat stress because of their exposure to sunlight, the strenuous nature of their work and the need to wear personal protective equipment (PPE). A man who worked on building projects in the UAE told the Vital Signs Partnership that the heat was so intense that sweat would leak from his boots. “Ten minutes after the bus dropped us off at the work site, I felt like life was exiting my body.”

In 2021, cleaners and security guards at the Dubai Expo center, which will host the COP28 conference, told the Associated Press of 70 hour weeks in the withering sun. One Kenyan security guard told the AP: “Work, sleep, work, sleep. There’s no freedom… You just need to try to survive one day to another.” When the Expo 2020 opened in October, well after the end of UAE’s summer working hours ban, tourists fainted from the heat. The human rights NGO Equidem last year reported comprehensively on forced labour and discrimination against migrant workers at Expo 2020.

Climate data and future projections

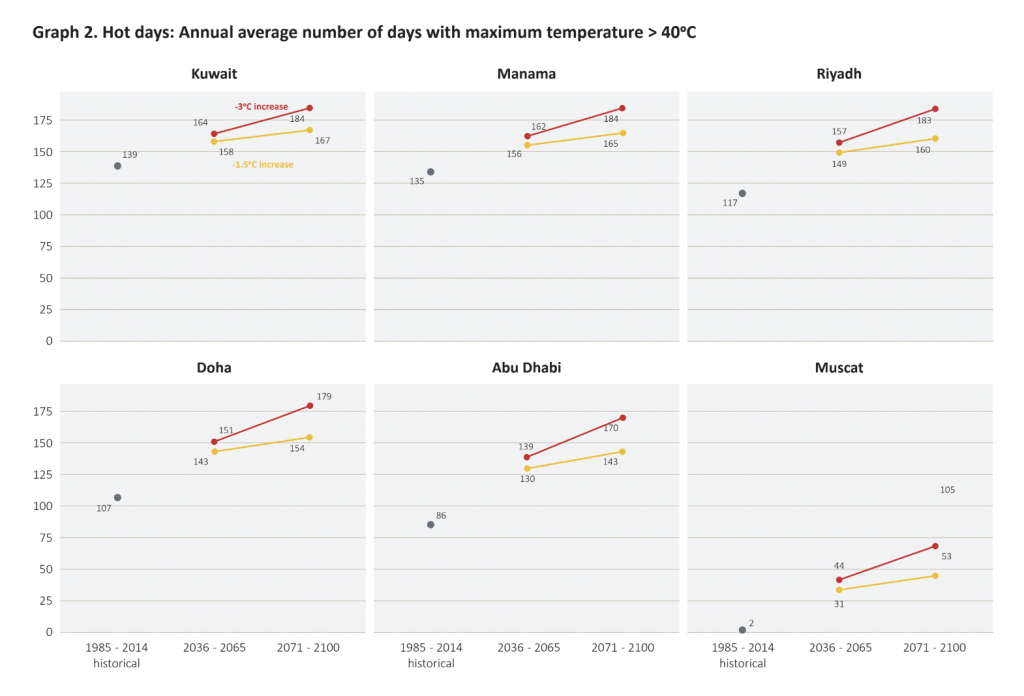

The Vital Signs Partnership commissioned Barrak Alahmad of the Department of Environmental Health at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and Dominic Royé of the Foundation for Climate Research (FIC) to analyse Gulf climate data, drawing on the latest state-of-the-art climate change projection models downscaled from NASA (NEX-GDDP-CMIP6). They found:

- In Abu Dhabi, the capital of the UAE, this year’s COP28 President, the number of days where air temperature exceeds 40ºC will increase by 51% by the middle of the century if global temperatures increases by 1.5ºC, and by 98% by the end of the century if they increase by 3ºC.

- A 3ºC increase will see Kuwait, Bahrain and Saudi Arabia experiencing 180 days out of 365 days where the temperature exceeds 40ºC by the end of the century.

- The Gulf region experiences dangerously hot night time temperatures, as well as extremely hot days. In June 2022 the temperature dropped below 30ºC only eleven times during 28 days, and was above 30ºC for 278 out of 290 night hours (between sunset and sunrise).

Barrak Alahmad told the Vital Signs Partnership that even under more optimistic mitigation scenarios like 1.5ºC these temperatures would markedly increase heat-related deaths in the region. “These conditions could seriously disrupt human societies in ways we are just beginning to understand.”

Chronic Kidney Disease

Global concern is growing regarding the development of kidney injury and chronic kidney disease (CKD) – a fatal, progressive loss of kidney function – in people who frequently perform physically demanding work in the heat. A nephrologist at Dhaka Medical College Hospital in Bangladesh told Vital Signs Partnership members RMMRU that he received many patients returning from the Gulf with kidney problems, attributing this to exposure to the heat and not consuming enough water to compensate for water lost as perspiration.

Sujan Thami, a 40-year-old worker from Nepal, worked as a plumber in Qatar in what he described as “searing heat” six days a week, often from the early hours of the morning until midnight, which left him “extremely exhausted”. He told the Vital Signs partnership that his accommodation resembled an “abandoned house”, without air-conditioning. At his workplace, 100 workers shared a single water point. After only nine months in Qatar, Sujan began to experience blurred vision, headaches,and vomiting, and medical tests revealed that his kidneys were not fully functioning and that he needed immediate dialysis. A kidney transplant is unlikely due to the cost. “I don’t know how much longer I will live,” says Sujan. “I may die at any time.”

Dr. Rishi Kumar Kafle, Executive Director and Chief Nephrologist at Nepal’s National Kidney Center told the Vital Signs Partnership that the numbers of Nepalese workers returning from the Gulf with chronic kidney disease was increasing and lamented the fact that poorer nations like Nepal foot the bill for costly dialysis, and that returnee migrants themselves have to pay for items like syringes, blood and iron.

“Nepali workers go to the Gulf to earn money, but return with kidney disease. Gulf nations are rich, they’re resourceful. They invite people from abroad to work for them. That’s okay, but they should provide safe working conditions. Why are these wealthy Gulf nations not doing anything for these workers?”

Lack of protection

None of the six Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states have laws that adequately mitigate the risk posed to outdoor workers by its extremely harsh climate. Each imposes a rudimentary ban on work at certain hours of the day during the summer months. The striking lack of consistency between countries underscores the unscientific nature of these measures. The UAE prohibits work for the least time of all the Gulf states, approximately half as much as Kuwait, and 40% of the hours banned in Qatar.

In May 2021, Qatar extended its ban on summer working hours to 588.5 hours a year and introduced additional legal measures requiring employers to mitigate the risk to workers from heat. These offer greater protection than the previous legal framework, but experts say they still fall significantly short. Professor David Wegman, an expert on health and safety, has described the Qatari legislation as “an improvement that falls far short of what is necessary”, emphasising the critical importance of balancing work and rest periods.

Lack of data

There is almost no data on the impact of heat on migrant workers in the Gulf. This is alarming given the well-established link between extremely high temperatures and increased rates of death.

The first Vital Signs report, published in 2022, found that of the approximately 10,000 deaths of migrant workers from south and southeast Asia in the Gulf annually, more than one out of every two are effectively unexplained, with deaths officially certified without any reference to an underlying cause, and terms such as “natural causes” or “cardiac arrest” appearing on death certificates instead.

C R Abrar, Executive Director of RMMRU and member of the Vital Signs Partnership, said:

“As the already brutal heat is likely to get worse, the Gulf states need to step up their approach to protect the millions of migrant workers who are so crucial for their economies. We are calling for ambitious action, including much stricter protective measures in the workplace, as well enabling workers to access adequate accommodation, nutrition and healthcare.”

For more information, see the dedicated Vital Signs website.