A major new report from FairSquare, published today, identifies serious structural flaws within FIFA, football’s global governing body, that have resulted in the organisation contributing to a wide range of social harms, not least very serious and systematic human rights abuses, and that preclude it from fulfilling one of its core stated objectives of developing the game.

Substitute: The case for the external reform of FIFA, a 174-page report based on extensive research, addresses FIFA’s governance practices and assesses the impact of its operations both before and after a set of critical governance reforms implemented in 2016. It concludes that there has been little to no improvement since these reforms, and that in some key elements of FIFA’s operations there has been obvious regression. The report argues that FIFA is not capable of self-regulation and that in the absence of external reform it will continue to cause or exacerbate human rights abuses and other social harms.

Nick McGeehan, co-director of FairSquare and lead author, said:

“FIFA is a commercial rights holder, a development organisation, a competition organiser, and a global regulator, all rolled into one big mess. Commercially, it’s a hugely successful organisation, but it has been grossly negligent in addressing the eye-watering list of human rights abuses linked to its operations, and from the perspective of the development of the game, most notably the development of the women’s game, it appears to be irredeemably dysfunctional.”

FairSquare works to promote better, more democratic governance to prevent sporting institutions contributing to harm and suffering. Our work on accountability in sport is informed by years of research and advocacy on abuses connected to the Qatar 2022 World Cup, and the role of FIFA. This report, which will be the first in a series, is rooted in the belief that sport has the potential to play a transformative, positive role in society, and the concern that too often its power is misappropriated and exploited. Football and FIFA provide the clearest and most urgent illustration of this alarming trend.

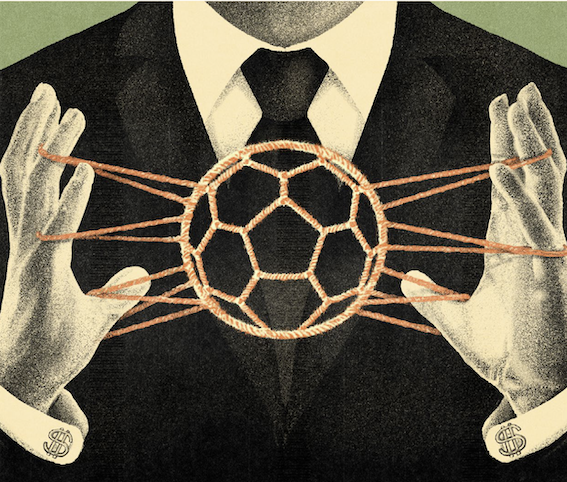

FIFA is structurally resistant to internal reform, the report argues, because its senior officials and a critical mass of its member associations are locked into a mutually dependent system of patronage, whereby FIFA’s development money is redistributed in such a way as to encourage the member associations’ political support for the President. This system makes effective self-regulation impossible and is at the root cause of the social harms that flow from FIFA’s misgovernance. The report’s central finding is that FIFA will remain unfit for purpose until this patronage network is broken up, if necessary via an institutional separation of FIFA’s various functions.

The report is based on more than 100 interviews with individuals affected by FIFA’s operations and a wide range of experts, including football administrators, human rights researchers, sociologists, economists, lawyers, experts in governance, corruption and tax. It draws on field research in Brazil and South Africa, as well as an extensive review of relevant FIFA and external literature. Its conclusions relate to the structural flaws that are at the root of its misgovernance and the social harms that flow from poor governance.

Structural flaws and impossibility of self-regulation

FIFA cannot effectively self-regulate itself because of structural flaws, which were built into the organisation. There is a critical lack of transparency over how member associations spend FIFA’s development funds distributed under the FIFA Forward Development Programme since 2016. In 2019, FIFA said it would subject all its member associations, upon whom the FIFA President relies for his political power under FIFA’s one-member-one-vote system, to independent external audits. However, there does not appear to be any public repository of these audits. The FIFA President has been granted excessive executive powers through the introduction of the Bureau of the Council to FIFA’s governance structure in 2016. FIFA has weaponised its prohibition of “political interference”, arbitrarily sanctioning or threatening to sanction FIFA member associations, when member associations or national courts take decisions that are out of line with the interests of the FIFA President.

These are the core elements of FIFA’s patronage system, which has scuppered all efforts at internal reform, most recently FIFA’s 2016 reform process. Immediately after this process, FIFA undermined independent oversight mechanisms, most notably in the case of the effective sacking of the head of the Governance Committee, Miguel Poiares Maduro, in 2017, and the dissolution of an independent human rights advisory board in 2021. In 2024, FIFA reversed key governance reforms introduced in 2016, significantly increasing the number of standing committees, and allowing its regional confederations to loosen or scrap presidential term limits.

Social harms flowing from poor governance

The outcome of these deep governance failings has been disastrous. FIFA’s operations entail very serious risks to a wide range of human rights and the organisation is guilty of serious due diligence failures, most notably in the run up to the Qatar 2022 World Cup, where it repeatedly failed to take steps to mitigate the serious human rights risks to migrant workers involved in preparations for the tournament. Its operations elsewhere have been linked to abuses including mass evictions, the destruction of livelihoods, police abuse, extrajudicial killings and other violations of the right to life, forced labour, and physical, sexual and psychological abuse.

FIFA’s failure to identify these risks and take steps to mitigate them has been abject. Beyond that, FIFA has even undermined its own human rights and social commitments by insisting that hosts of its World Cups suspend or provide FIFA with exemptions from domestic labour laws, and has deprived developing country hosts of hundreds of millions of dollars of tax revenue by demanding tax exemptions for itself and its partners. The organisation most recently manipulated its own World Cup bidding guidelines to enable Saudi Arabia to be the sole bidder for the men’s 2034 World Cup and played a role in arbitrarily limiting the scope of an independent human rights context assessment of Saudi Arabia to exclude a large number of highly relevant human rights.

FIFA has failed to take meaningful steps towards gender equality in football governance and has failed to institute effective measures to mitigate the risks of physical, sexual and psychological abuse, most notably in the case of its failure to institute a safe sport entity despite having committed to doing so.

External reform

In relation to the critical question of how FIFA can be reformed, as FairSquare outlined in a recent policy brief, Laws for the Game, co-authored by Dr Jan Zglinski from the London School of Economics, the European Union offers one possible solution. The EU has the competences to regulate FIFA (and sports governing bodies more generally), its laws are binding and can be drafted in a way as to have an external effect beyond Europe’s borders, and, as a political union of 27 states, it is far less susceptible to political pressure from FIFA. The policy brief describes the various ways in which a dedicated EU law on sport could impose the type of effective governance that is conspicuous by its absence at FIFA and which internal reforms in 2012 and 2016 failed to address.

“Football is far too socially, politically and economically important to be governed this poorly. Only external regulation will provide the foundations for FIFA to deliver on football’s transfomative potential and to prevent the organisation from causing more serious harm”, said Nick McGeehan.

Post-publication note: FIFA Response

FairSquare wrote to FIFA President Gianni Infantino prior to publication, on 7 October 2024, with a summary of the report’s key findings, and to provide FIFA with the opportunity to respond.

On 31 October 2024, the day after the publication of the report, FIFA’s Chief Legal and Compliance Officer sent FairSquare a lengthy response stating that the report “misunderstood and mischaracterised many aspects of FIFA’s purpose and its organisational and governance structure”. FairSquare offered FIFA the chance to provide further information on the issues it raised in this communication. It has not done so.

In relation to one of the points raised by FIFA, FairSquare made two minor modifications to the report.