FairSquare, working with Human Rights Watch, has been documenting the case of Abdullah Ibhais since late 2021. His lawyer filed an appeal with Qatar’s final court of appeal, the Court of Cassation, on 13 February 2022. In this piece FairSquare Director Nick McGeehan provides analysis of the key pieces of evidence in the case.

Abdullah Ibhais, a former Media Manager within Qatar’s World Cup organising committee, the Supreme Committee for Delivery and Legacy is currently in jail in Qatar, serving a three-year jail sentence for bribery. He claims that he has been the subject of a malicious prosecution in response to his efforts to stand up for migrant workers’ rights. The Supreme Committee say that this is “ludicrous”, but have not made clear the central role they played in the case and, like FIFA, have failed to make a call for Ibhais to receive a fair trial. So what does the evidence show and tell us about the case? Here are the four key pieces of evidence to help you cut through the spin and understand what is going on and why the case deserves attention.

The Whatsapp Chat. 5 August, 2019

In August 2019, a large group of migrant workers in the Al-Shahaniya labour camp outside Doha went on strike in protest at unpaid wages. When media in the UAE reported that the strike involved workers building stadiums for the 2022 World Cup, Qatar’s World Cup organisers discussed how best to respond on an internal whatsapp chat.

What does it show?

Ibhais provided evidence to his colleagues and his superiors that some of the workers were actually involved in 2022 stadium construction and were in dismal conditions as a result. He did this in response to claims from some of his colleagues that the strike did not involve Supreme Committee workers and that it had been resolved. Ibhais and a colleague posted footage of the workers that they had filmed themselves. Ibhais also advised that the Supreme Committee should publicly acknowledge the involvement of their workers and focus on remedying the situation. “Lying is not Qatar’s way, and should not be,” he told his superior in one message. The Supreme Committee arranged for the workers to be paid, but denied that their workers were involved.

What does it tell us?

The conversation shows that Ibhais was unafraid to challenge senior colleagues on very sensitive matters. His intervention directly contradicted information provided by other senior members of the SC. His advice that the SC should acknowledge the involvement of its workers could have been seen by some within the SC as exposing the SC and Qatar to criticism, including from media outlets operated by its regional adversaries, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

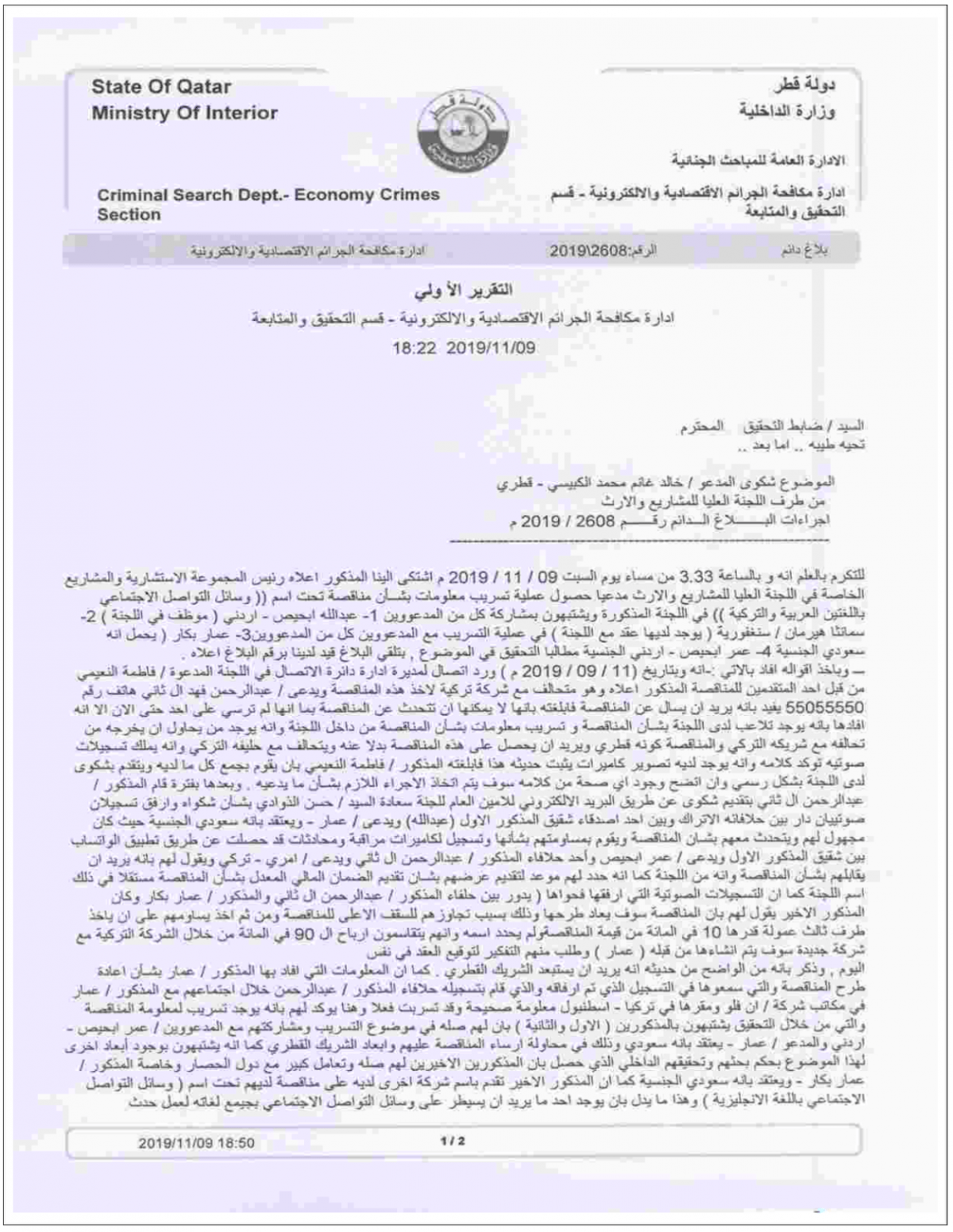

The Police Report. 11 November, 2019

The case against Ibhais has its roots in an internal investigation report submitted by his employers to the Qatari police on 9 November 2019. The police report summarizes the findings of the Supreme Committee’s internal investigation.

What does it show?

It states that the internal investigation was initiated after a member of the ruling Al-Thani family in Qatar called Abdullah’s direct superior and told her that he had evidence that Abdullah and his brother had conspired with a Saudi national to exclude him from a tender for a social media contract. Perhaps more importantly, it said that Abdullah’s brother and the Saudi national “have a connection and affairs with the embargo countries, particularly Ammar Bakar.” (Although the report does not state this, Ammar Bakar is a senior figure in Saudi Arabia media circles). The police report states that the SC suspects that “someone wants to control the social media in all its languages to prepare an action or something that harms the State or its security through the aforementioned social media tenders.” and that the SC “ request investigation on the issue to ensure that there is no intention by the aforementioned to harm the State, its reputation or security.”

What does it tell us?

It shows us that the investigation was instigated by the Supreme Committee because a member of Qatar’s ruling family called Ibhais’s superior and said that he had evidence that people had conspired to exclude him from a social media contract, and requested her intervention in the matter. More critically, it shows that the investigation into Ibhais went beyond allegations about the procurement process for a contract – it was raising suspicions, genuinely held or otherwise, that Ibhais and his brother were trying to allow a Saudi media figure to have control over Qatar’s 2022 World Cup social media accounts. This at a time when Saudi Arabia had cut off all diplomatic and economic contacts with Qatar. This explosive allegation, which it provided no credible evidence to support, lends credibility to Ibhais’s claim that after his arrest on 12 November, 2019, interrogators and prosecutors threatened him with state security charges, and that it was his fear of a State Security detention and implied threats of torture – “either you sign a confession here or we send you to State Security, where they know how to get a confession out of you”, one interrogator told him – that led to him signing a confession to the lesser charge of bribery.

The Court Judgements. April 2021 and December 2021

Ibhais was convicted of “bribery,” “violation of the integrity of tenders and profits,” and “intentional damage to public funds,” and received a five-year prison sentence and a fine of 150,000 Qatari riyals (US$41,197) on 29 April. On 15 December, Qatar’s court of appeal upheld the conviction but reduced the sentence to 3 years.

What do they show us?

The evidence against Ibhais was his confession, and evidence provided by the testimony of five witnesses. The court refused to examine Ibhais’s allegations that his confession was coerced and said they believed it was accurate, even though Ibhais said it was not. The court said it has full discretion “to decide whether a confession is valid or not at any stage of the investigations” regardless of whether the accused recants the confession in court. The court stated that it was assured of the authenticity of the confession. The appeal court found similarly.

No physical evidence was produced in evidence against Ibhais. The testimony provided by witnesses shows that neither the Supreme Committee nor the police found any evidence that Ibhais had committed any crime. In his witness testimony in the first trial, the Supreme Committee’s internal investigator, Khalid Al-Kubaisi, acknowledged that their internal report did not conclude that Mr Ibhais had committed any crimes. Mr Al-Kubaisi also said that it was “not within the jurisdiction of the investigation committee” to verify audio evidence that the Supreme Committee has claimed implicates Mr Ibhais in wrongdoing and which was apparently provided to them by the member of the ruling family whose complaint instigated the case. The sole police officer charged with investigating the allegations told the court that he had not investigated the authenticity of the recordings, saying “that is not my specialty.” When asked for details of what his investigation had uncovered in relation to alleged leaks of information attributed to Mr Ibhais, he replied “I don’t know.” When asked if his investigations found that Mr Ibhais leaked information pertaining to the case at hand, the police officer replied “No.”

What do they tell us?

The trial hearings have been grossly and absurdly unfair. Neither considered or reviewed any actual evidence, and instead blindly accepted a confession despite Ibhais’s retraction, his serious claims of police and prosecutorial misconduct, and the absence of any corroborating evidence.

The Evidence Against Ibhais

The Supreme Committee has repeatedly made claims in public and in private that it has evidence that Ibhais was involved in wrongdoing. In a statement to the BBC the Supreme Committee, for example, it said that it had collected “audio and visual documentary evidence” to support the allegations against him.

Where is this evidence?

In the appeal hearing, Ibhais’ lawyer asked the appeal court to review the evidence that the Supreme Committee claims exists as proof of Ibhais’ wrongdoing – voice notes, video recordings, and WhatsApp messages between Ibhais and other defendants in the trial. The appeal court refused, saying that it was satisfied with the evidence provided to the Court of First Instance despite the fact that the Court of First Instance did not consider this evidence. So no evidence was produced in court and none has been produced since, although They have repeated this to NGOs and numerous journalists.

The Supreme Court has made redacted copies of the internal investigation available to select journalists, but not the evidence it says supports its claims. The focus of the Supreme Committee’s efforts have been to argue that Ibhais was not a champion for workers’ rights. In their statement to the BBC they said the SC said that “Mr. Ibhais’ post-conviction allegations that the SC conspired against him because of his views on migrant workers are ludicrous, defamatory, and absolutely false.”

What does this tell us?

The evidence shows that a young man with a wife and two young children is facing three years in a Doha jail despite no evidence he has done anything wrong and a grossly unfair trial. The fact that he took a bold stance on migrant workers’ rights and stood up for the workers building stadiums for the Qatar 2022 World Cup only a few months before his arrest may just be a remarkable coincidence. Whereas there is a considerable body of consistent evidence to support Ibhais’s version of events, there is literally no evidence to support the SC’s claims against him.