In an article for the European Council on Foreign Relations, FairSquare co-director James Lynch warns that scything cuts to US foreign aid will drain an already shallow pool of funding for embattled human rights defenders and independent media. That should worry Europeans, whose own budget cuts are part of the problem.

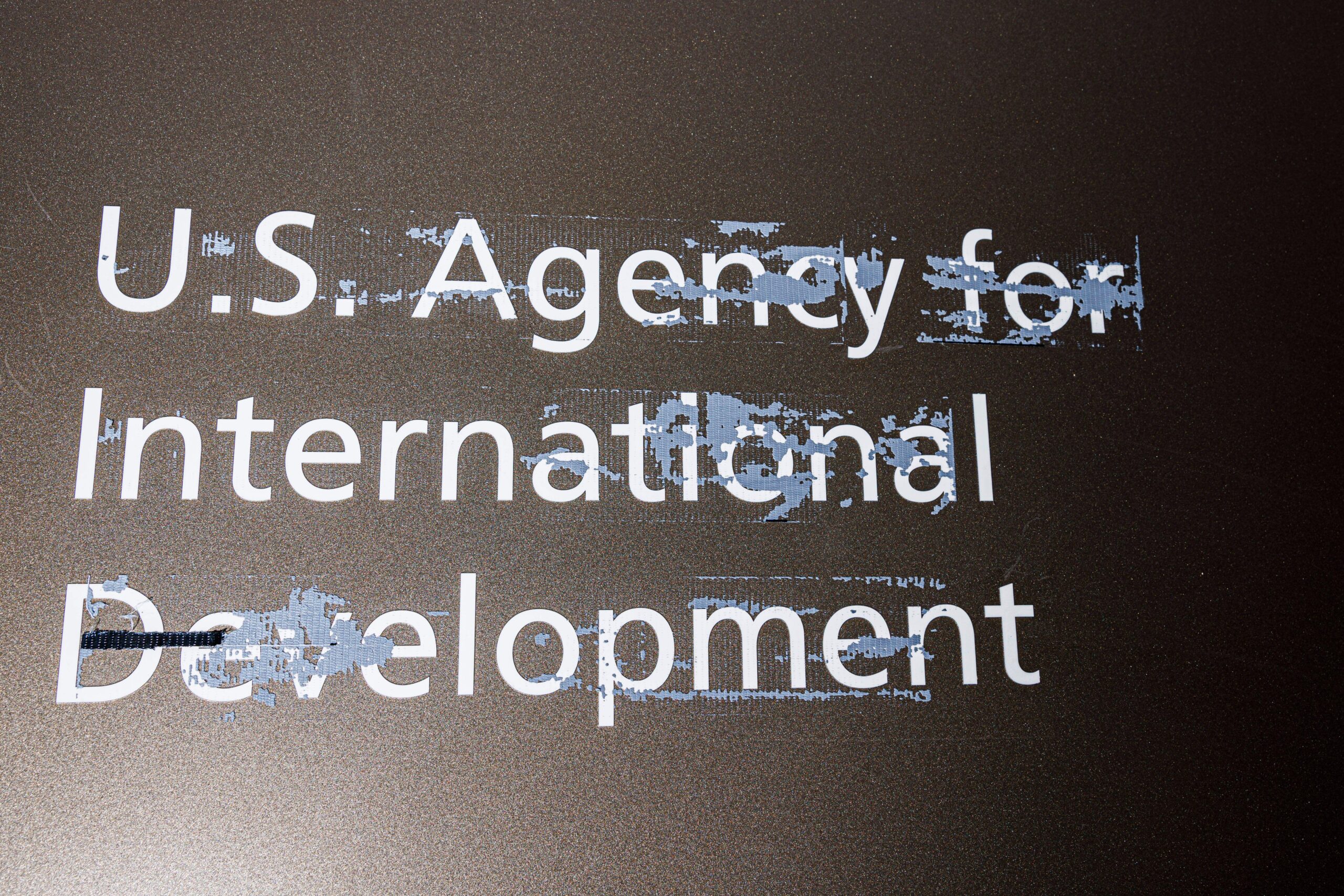

The American government’s immediate pause on almost all of its foreign aid has sent shockwaves around the world. It comes at a time when democracy and human rights are under relentless attack, from the West Bank to Washington DC. The activists and organisations that defend these values were already facing a funding crunch—including from European sources.

The US cuts will compound this crunch most in places where it is difficult or impossible to sustain local fundraising due to restrictions on free association, such as in highly repressive states in the Middle East. Without an active civil society in the EU’s southern neighbourhood, largely unaccountable governments will be even freer to pursue destabilising policies: budgets will go unscrutinised, abuses will go undocumented and alternative perspectives will go unheard. It is in the interests of Europeans to urgently consider what they can do in this moment of crisis to provide a lifeline.

Funding uncertainty

More than $2bn of American foreign aid each year goes to programmes under the headings of democracy, human rights and governance. All of this spending is paused for “review”.

The Trump administration should not be able to unilaterally stop or even pause spending. Congress has control over the taxing and spending of public money—the “power of the purse”. Republican lawmakers, who have a narrow majority in both houses of Congress, have traditionally supported democracy programmes such as Near East Regional Democracy, which provides around $65m each year to support Iranian opposition and civil society groups. During the Joe Biden administration, the Republican-controlled House passed a bill to provide $2.9bn for “democracy programs” for the 2025 fiscal year. A political tussle is likely over at least some components of this package.

The 90-day pause and associated “stop work” orders have so destabilised some smaller and dependent organisations—from media outlets to technology activists and anti-corruption campaigners—that many may not recover even if their funding is restored

Nevertheless, it is difficult to envisage an outcome that does not ultimately reduce American democracy and human rights funding. Trump’s head of the “department of government efficiency”, Elon Musk, has described one of the country’s most significant funding bodies, the National Endowment for Democracy, as a “scam”, for example. The State Department has reportedly fired about 60 contractors who worked for its democracy, human rights and labour bureau. The 90-day pause and associated “stop work” orders have already so destabilised some smaller and dependent organisations worldwide—from media outlets to technology activists and anti-corruption campaigners—that many may not recover even if their funding is restored.

This problem is particularly acute in the Middle East and North Africa. According to one funder I interviewed, the US has about 150 active democracy and human rights grants in those regions—disproportionately more than other parts of the world. Most of these grants are split between multiple organisations, meaning that the freeze affects several hundred groups. The funder said they were receiving 10-15 messages a day from groups seeking assistance for laying off staff and considering shutting down operations.[1] On top of the immediate impact, even organisations that do not receive US funding will be affected. This is because the total pool of funds available for democracy and human rights will shrink, creating more competition for a smaller amount of money.

A shrinking pool of funds

That pool had anyway been getting shallower before the latest American actions. As noted by Coline Le Piouff for ECFR, Europe has seen a wave of dramatic “slash and burn” general aid cuts by leading donors such as Britain, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden. Governments seeking to reduce spending in the wake of covid-19 targeted foreign aid. They subsequently redirected funds to the Ukrainian government and domestic refugee programmes. Political support in European countries for funding civil society has also weakened as a result of deepening polarisation, with right-wing political parties alleging that NGOs are too close to the left and should not be funded to advocate.

As aid budgets tightened, funding for democracy and human rights was deprioritised: one 2024 study found that EU member state funding for the Middle East and for North Africa was shifting from human rights to other priorities such as migration. In 2023, the EU allocated just €2m in democracy and human rights aid programming to the region—“virtually nothing for a huge region still roiling with local social movements and protests”, according to one Carnegie report. Private philanthropy has also been pivoting towards challenges such as climate change and AI, with human rights funding beginning to resemble “a lunar landscape”, in the words of one commentator.

Re-evaluating funding priorities

Some activists in the Arab world have in recent years raised the prospect of ending their relationship with Western funding, on the basis that it has become increasingly unreliable and politically unpalatable. Nonetheless, the short-term financial shock of the US decision will leave many groups on the brink, as the groundwork for alternative sources of funding has not yet been laid. Collapse could happen with the wider world barely noticing: affected organisations are, in many cases, unlikely to speak publicly about the impact of the freeze because they do not want to be associated with the deeply unpopular regional policies of the United States.

It would be unrealistic to expect European countries to replace American support, but they can provide immediate assistance by identifying at-risk grassroots US grantees and supporting them with flexible, unrestricted funding that is free of co-funding requirements and red tape. As the outlook in Washington becomes clearer, the EU should re-evaluate more deeply its support for civil society in its southern neighbourhood, with a view to developing reliable, less politicised funding mechanisms. Without these groups, Europeans risk losing partners they see as key bridging interlocutors, who can offer them privileged access to communities and perspectives otherwise beyond their reach.

The EU and its member states should also reconsider their recent “defensive turn” that has seen them prioritise funding for democracy work that is less visibly rights-based. This approach may be misaligned to the urgency of the challenge. With the rule of law facing existential threats from a multitude of directions, Europeans can play a vital role by supporting those working at the coalface of its defence.